There’s nothing as grand as when one of your candidates accepts an offer. And there’s nothing as miserable as when that same candidate turns around and declines the same offer.

Wait, what? How does that happen? Why does that happen? How can you stop that from happening?

Why does a candidate rescind job acceptance?

Our story starts with the fact that we’re in a candidates’ market. In such a market, all job seekers and candidates have more options. Not only that, but the best job seekers and candidates have the most options. That’s because more companies and organizations want the best candidates to work for them.

As a result, top candidates have no qualms about exploring multiple opportunities with multiple employers. They could be involved in the hiring process of two, three, or more companies. (In fact, one recruiter told me last year they had a candidate who was interviewing with seven organizations and received offers from all seven! When did they find time to sleep?)

So you can imagine how this scenario plays out. A candidate receives an offer of employment and decides to accept it. However, since they’re immersed in the hiring process of another organization, that employer also presents them with an offer. And it just so happens to be a better offer than the first one. So what does the candidate do?

The candidate does what they believe to be in their best interests: they accept the second offer and they decline the first one . . . after initially accepting it. They went with the “BBO” . . . the “bigger, better offer.”

Is it ethical to do that? From the hiring manager’s perspective, they would probably say, “No, it’s not.” From the candidate’s perspective, they would probably say that it’s a “gray area.” How gray, candidate? “Charcoal,” they would respond.

Ultimately, though, none of that matters. What does matter is what you, the recruiter, can do about all of this.

The short answer: not much, after the fact.

Rejecting a job offer after signing the offer letter

Let’s talk about before the fact, shall we? The initial offer to the candidate is usually a verbal one, made by either the hiring manager or the recruiter if the organization used one for the search. Regardless, the verbal offer is typically followed by a written offer letter. The candidate is expected to sign the written offer letter as a gesture of goodwill.

But . . . is that signature and the corresponding document legally binding?

In a word, no . . . not really. If the offer letter is paired with some kind of contract, then perhaps there are some legal ramifications. But these instances are rare in the world of employment, especially for positions that fall outside of the C-suite.

Actually, the more common situation is when a candidate signs an offer letter and then the company rescinds the offer. The candidate mistakenly believes that they have a legal right to work for the organization because they signed the offer letter. However, for the purposes of this blog post, we’re discussing a situation in which the candidate and not the company changes their mind.

So can company officials then sue the candidate to force the candidate to work for the organization? Even if the candidate signed an offer letter and a corresponding contract that would allow the company to do such a thing, would that really be of any benefit? Consider the following:

The company would basically be “forcing” the candidate to work for it. The candidate would be working for the organization against its will. How long do you think it would be before the candidate quit?

Let’s say that not only was the candidate required to start work for the organization, but they were required to work there for a certain length of time. What kind of attitude do you think they would have? Answer: probably a poor one. How would that attitude affect other employees?

Would the candidate, if forced to work for the organization, ultimately try to get fired, just to be rid of the situation?

How does any of this benefit the company? It doesn’t. Basically, it’s not worth forcing the candidate to start work, even if the organization has the legal leverage to make it happen. So . . . company officials just let the candidate go. Hopefully, they can make an offer to their #2 candidate, the runner-up who is now the top choice.

And then, of course, there’s you, the recruiter. Your candidate was hired and almost started work. You almost received a placement check. You almost earned a fee. Almost. Sigh.

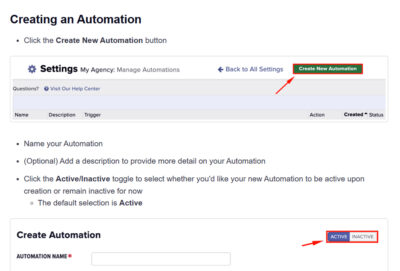

Preventing a candidate from declining a job offer after accepting

So how can you prevent all of this from happening?

You close the candidate. And then you close them again. And again and again. The candidate is never truly closed until you have collected your placement fee and the guarantee period has ended. Then they’re finally closed.

From the recruiter’s perspective, it all comes down to closing candidates in a competitive market. And Top Echelon has already devoted an entire blog post to that topic, titled “How to Close a Candidate . . . When It’s a Candidates’ Market.” In that post, we cited seven specific steps for closing a candidate (and keeping them closed):

- Identify the REAL pain points early in the process.

- Pre-close the candidate using those pain points.

- Keep closing throughout all stages of the process.

- Do everything you can to shorten the process.

- Make the offer as soon as the client has decided that it wants to make the offer.

- “Sell the socks” off the offer.

- Make the candidate feel wanted.

But is that enough? Is there more that you can do to prevent the nastiness associated with a candidate who changes their mind. Thankfully, there is! And all it involves is asking some specific questions prior to the offer stage of the process. Those questions are as follows:

- “If the company makes an offer and you accept it, will you accept an offer from another organization if another offer is made to you?”

- “If the company makes an offer and you accept it, will you accept a counteroffer from your current employer if one is made to you?”

Sounds like easy enough questions. You might be asking yourself what the point of these questions are. After all, the candidate could easily lie. However, that’s exactly the point. There are only a few different ways that this can play out:

- The candidate can say that yes, they will accept another offer or a counteroffer. If that’s the case, then you caution your client. (I know, I know. What are the chances that’s going to happen?)

- The candidate could say, no they will not accept another offer or a counteroffer. Then they accept the offer from your client and do NOT accept another offer or counteroffer. If that happens, all is well!

- The candidate could say, no they will not accept another offer or a counteroffer. Then they DO accept another offer! What the heck? This is what we wanted to avoid!

Calm down. Here’s the beauty of asking these questions. By asking them, you’re basically forcing the candidate to make a quasi-commitment to your client’s offer. Sure, they could still bail on you, but they would have to make a liar of themselves in the process. They would have to sit there and think the following thoughts:

“Gee, this new offer is better. But I flat-out told that recruiter I would not accept another offer. If I accept this one instead, then I’ll be a liar. I pretty much lied right to their face. You know what? I don’t care. I don’t care if I lied and everybody thinks I’m a liar. I’m going to take this other job instead.”

And if that’s what they’re going to think and that’s what they’re going to do, does your client really want to hire them? And it covers you, as well. You can say to the hiring manager, “I asked the candidate point-blank if they would accept another offer after accepting your offer and they said no. So they lied.”

The bottom line is that candidates are less likely to lie and go back on their word if they’ve already stated that they would NOT go back on their word. It can still happen, yes, but it’s less likely.

That’s not a whole lot of ammunition, to be sure, but when combined with the other steps listed above, it’s something. And in a candidates’ market like this one, you need all the ammunition you can get.

(Editor’s note: the information provided in this blog post should NOT be construed as legal advice. If you have specific questions about this topic, consult your legal counsel.)